|

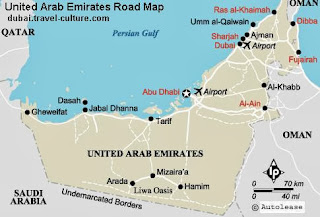

| road map of the United Arab Emirates showing the triangle of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and Al Ain |

Our first trip to Dubai was in the fall, just after all the family members of expatriate workers, who abandonded the peninsula for the summer, returned. Also, coincidentally right after a number of roads had been added or rerouted within and around Dubai. We got lost on our way to the souq in Sharjah, one of the smaller emirates of the seven that constitute the United Arab Emirates, and even the traffic police couldn't tell us which way to go. Sharjah was adjacent to Dubai and had one of the most modern souqs in the country. It was also the home of Pinky's a set of three warehouses where the owner stored items he imported from India for his shop which had been in the downtown Dubai souq. When the owner of Pinky's learned several years earlier that the old souq was going to be replaced by a modern souq, he closed up his shop in anticipation of the old souq being destroyed, but that still hadn't happened. But the three warehouses gave him so much more room, he never looked for new space. Instead, he welcomed shoppers to the warehouses which were so crowded with stuff that just walking into them was an adventure. There were treasurers to be found everywhere.

|

by J I G I S H A by J I G I S H Aa.k.a Nitin Badhwar |

We often headed out on the weekend for breakfast either in Dubai or Al Ain. The Jumeirah Beach Hotel opened in 1997 and offered a spectacular location for Friday (Gulf Sunday) brunch with its view of the Burj Al Arab, a companion hotel located off the coast on a man-made island.

Al Ain was an oasis city, the original home of the then leader of the U.A.E., Sheikh Zayid bin Sultan Al Nahyan. Flowers, especially roses, lined the roads of Al Ain, making it a garden in the desert. Lucent had a hotel suite permanently rented there for its staff when work needed to be done in that area. More than once, I went with Alex and while he worked, I spent the time around the pool at the hotel.

The two Eid holidays begin when the religious leaders of the country see the new moon or otherwise determine when the holiday begins. Most countries on the Arabian peninsula follow whatever the religious leaders in Saudi Arabia declare. Our friends told us that Oman, however, did not. Oman had its own designated religious leaders who declared when the holidays began. Their religious leaders always seemed not to see the signs until the day after the leaders in Saudi Arabia. But since so many people traveled internationally to be together with family for these important holidays, the Omani government gave employees the day before the holidays began off. A neat trick, right?

We also spent time in Muscat with friends. A couple we met through Doha Players, Alf and Gina, had moved to Oman from Doha. And my friend Gloria, the ambassador's secretary in Doha, was also on assignment with the embassy in Muscat.

Our travels to Oman were the only trips where we couldn't get unleaded gasoline for our car. We filled the tank in Al Ain and hoped we wouldn't run out before returning to the U.A.E. If we ran dangerously low, we would add a few gallons, but never fill it.

In 1998 the embassy was still in the same building I knew although a number of temporary buildings had been added along the edge of the compound where all the administrative functions were now housed. The main building had been turned into a controlled access area which required everyone to be escorted within. We never went in. But we thoroughly enjoyed walking through the places we enjoyed so much when we lived there - the Center, the Caravan restaurant, the Sheraton Hotel, and the ring roads. We also went to the mall which had opened since we left Doha. In contrast to the elaborate and exotic and over-the-top malls in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, the mall in Doha could have been in any midwestern U.S. town, just one more reason that we enjoyed living in Doha. It was a small town, just like the small towns we had grown up in, with just enough exotic foreignness to make living there an adventure. |